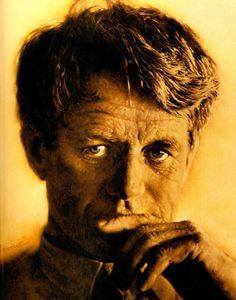

The Following was posted to David Talbot’s Facebook homepage today, 10 June, 2024:

We’re saddened to inform you all that David has suffered a near-fatal stroke. It happened as he and his wife, Camille, were having to move out of their family home of 30 years, and it’s left both David and Camille in a scary and precarious place, not knowing where they’ll live on top of this agonizing event.

We’re saddened to inform you all that David has suffered a near-fatal stroke. It happened as he and his wife, Camille, were having to move out of their family home of 30 years, and it’s left both David and Camille in a scary and precarious place, not knowing where they’ll live on top of this agonizing event.Fundraiser by Connie Matthiessen : Help David Talbot After A Severe Stroke (gofundme.com)