Mr. Kick’s interests extended from “undeleting,” as he sometimes called his document gathering, to classic literature, erotica, food and ancient meditation practices. “I can’t focus completely on any one thing for too long,” he wrote in an online biography. “My personal brand is a mess.”

Driven in part by a distrust of authority and an obsession with trivia, he wrote news articles for the Village Voice and edited myth-busting books such as “You Are Being Lied To” (2001) and “Everything You Know Is Wrong” (2002), which brought together the voices of scholars and journalists — including Howard Zinn and Noam Chomsky — to correct “media distortion, historical whitewashes and cultural myths.”

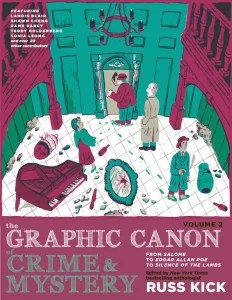

Kick edited “The Graphic Canon,” a book series that reimagined literary works as comics and visual art, as well as a spinoff series, “The Graphic Canon of Crime & Mystery.” (Seven Stories Press)

He also edited literary anthologies and the Graphic Canon series, for which he enlisted artists such as Robert Crumb and Will Eisner to reinterpret literary classics as comics and visual art. By turns bawdy and poignant, the series marked a kaleidoscopic alternative to the giant, doorstop literary anthologies published by W.W. Norton. “Work that might normally put you to sleep will leave you awe-struck,” artist and author Annie Weatherwax wrote in 2012, reviewing the first volume for the New York Times.

Mr. Kick’s work on the book series marked a temporary departure from some of his abiding interests: crusading against government secrecy and holding powerful people and institutions accountable. “I’m certainly not a journalist in the normal sense of the word,” he once told the Times. “I’m more of an information archaeologist. I’m trying to get the stuff that’s either been purposely buried or just covered over by time.”

Working largely on his own, without institutional support, Mr. Kick filed FOIA requests to obtain documents related to U.S. biological and chemical warfare programs, U.S. Border Patrol facilities, animal experimentation and a host of other issues. “Oftentimes it was those mundane requests that would be a critical resource years down the line,” said Michael Morisy, the co-founder and chief executive of MuckRock, a nonprofit news site where Mr. Kick had worked the past two years.

In an email interview, he added that Mr. Kick was “omnipresent” in the FOIA community, “the person you’d turn to every time there was a question about document arcana or the ins-and-outs of obscure filings.” Mr. Kick was also known as one of the first to regularly publish original documents in full, rather than to simply share quotes or transcriptions, according to Washington Post FOIA director Nate Jones.

“He influenced this generation of FOIA requesters by showing the power of posting the records unvarnished and letting them speak for themselves. . . . His sites were completely dedicated only to that,” Jones said. “I suspect the hosting fees were quite high, yet nonetheless he was a declassified document posting machine.”

Mr. Kick started publishing documents in earnest in 2002, on a website he called the Memory Hole. Its name was a kind of reverse homage to the incinerator used to destroy embarrassing government files in George Orwell’s “1984.” (In later years, he created the websites Memory Hole 2 and AltGov2 to share his work.)

Among his first major releases was an unredacted internal report from the Justice Department, documenting harsh criticism of its diversity efforts. When the report was first published on the department’s website in 2003, half of its 186 pages were blacked out. Mr. Kick simply downloaded the file, opened it in Adobe Acrobat and used the “TouchUp Object” tool to highlight and delete the black bars.

“It was that simple,” he told the Times. “I was kind of surprised, but we are talking about a government bureaucracy, so I wasn’t that surprised.”

Six months later, Mr. Kick made headlines by publishing Pentagon photographs of the coffins of troops killed in Iraq and of service members caring for the remains of their fallen comrades, which he obtained through a FOIA request. The Defense Department had previously barred the publication of such photos and called their release a mistake.

Their publication on the Memory Hole, and later in newspapers and on TV networks including CNN, ignited a national debate over access to wartime images, the privacy of military families and the human cost of war. “I’ve always thought that war should not be sanitized and airbrushed,” Mr. Kick told NPR, explaining his decision to publish. “I think people should see what the real results of war are.”

In a phone interview, BuzzFeed News investigative reporter Jason Leopold said the publication of the Iraq War photos inspired his own use of FOIA requests, often for documents that he had never previously thought to seek. “I remember thinking to myself, ‘I want to duplicate that. I want to get documents,’ ” he said. “Russ went after records that we as journalists never went after, because we felt we would never get them.”

Russell Charles Kick III was born July 20, 1969, in Tuscaloosa, where his father was studying for a PhD in business and computer science at the University of Alabama. His mother was a homemaker, and his father later taught at Tennessee Technological University in Cookeville, where Mr. Kick graduated from high school.

Both parents had grown up in strict Catholic families before rebelling against organized religion — his father wrote a spiritual text called “The Key to Self-Discovery” — and encouraged their children to read widely, from Isaac Asimov novels to books about Eastern philosophy. “Most parents worry that their kids are going to grow up and join some cult,” his sister Ruth said. “My mom worried we were going to join the Catholic Church.”

Mr. Kick graduated from Tennessee Tech with a bachelor’s degree in psychology, then studied for a master’s degree in public policy at Vanderbilt University in Nashville before dropping out to focus on writing. “I started reading, writing, and over-collecting books at an early age and just rolled with it,” he later wrote. “I’ve always been interested in important things that are suppressed, ignored, or simply forgotten, so those became my themes.”

In 2017, he revealed that U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials had asked for official permission to destroy old documents about the deaths and sexual assaults of detained immigrants in their custody. Organizations including Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington sued the National Archives and Records Administration to block ICE’s plan to destroy the records. A federal judge ruled in March that the agency could not destroy the files.

“I do get angry when it’s obvious somebody is lying to us, or keeping something from us,” Mr. Kick had told the Los Angeles Times in 2004. “I take it personally.”

His marriage to Kimberly Gannon ended in divorce. In addition to his sister, of Oro Valley, Ariz., survivors include his mother, Jane Woody Kick, of Tucson.

David Cuillier, a University of Arizona professor who studies government transparency and public-records access, said Mr. Kick’s records requests “demonstrated that anyone could use FOIA to show the public what the government is up to.”

“His work has inspired other average people and journalists to push for government transparency,” he added in an email. “That has made the country stronger — in holding government accountable. What he did wasn’t easy, especially on his own time without institutional support. But it made a difference.”