He had faced accusations that, as interior secretary, he was responsible for repressing protests before the 1968 Olympics that ended in a massacre.

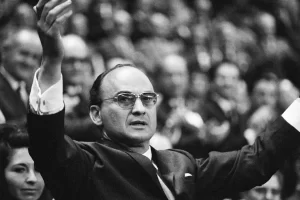

Luis Echeverría Alvarez in 1969 as he accepted his party’s nomination for president. He steered the country on a left-wing course, but his tenure was shadowed by his role in a massacre at the Olympic Games. (Photo credit: AP)

Luis Echeverría Alvarez, who steered Mexico on a stormy left-wing course in the 1970s as president and who never escaped the shadow of a massacre before the 1968 Olympics, died on Friday at his home in Cuernavaca. He was 100.

His death was confirmed in a tweet by President Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

Under Mr. Echeverría, the number of government employees tripled, state-owned businesses multiplied almost eightfold, and inflation exploded, undermining years of relative economic stability.

But Mr. Echeverría may best be remembered for accusations that he was largely responsible, as interior secretary, for the repression of student-led protests in 1968 before the Mexico City Olympic Games that culminated in the killings of scores of people, perhaps as many as 300.

Nearly four decades later, he was placed under house arrest when the case was revived, a spectacular turn for a former president.

The aftermath of the massacre helped shape his presidency, which began in 1970. Seeking to make amends, he brought left-wing intellectuals into the government, gave the government broad control over the economy, and embraced third world positions in international affairs. These measures alienated the business community, the middle class, and other politically conservative groups.

By the time he left office, Mr. Echeverría was being denounced by critics across the political spectrum, accused of authoritarianism and incompetence, and assailed for policies that provoked a flight of capital abroad, a steep devaluation of the peso, and economic stagnation.

Nonetheless, he campaigned for a Nobel Peace Prize and harbored hopes of becoming secretary general of the United Nations.

Born on Jan. 17, 1922, in Mexico City, the son of a civil servant, Mr. Echeverría in many ways typified the so-called “second generation” of the political elite who emerged from the country’s bloody revolution.

In the decades after that upheaval, politics was dominated by former officers of the revolutionary armies. But by the 1940s, a degree from the prestigious law school of the National Autonomous University of Mexico had become the surest passport into politics.

After graduating from that law school, Mr. Echeverría allied himself with a strong political family by marrying María Esther Zuno, the daughter of the governor of the state of Jalisco, with whom he had eight children. He then looked around for a powerful mentor, another prerequisite for aspiring politicians. He became a protégé of Gustavo Díaz Ordaz, a cabinet minister and former state governor who was clearly headed for the presidency.

When Mr. Díaz Ordaz was elected president in 1964, he appointed Mr. Echeverría as his secretary of interior, the cabinet official in charge of domestic political affairs. That post assured him of succeeding Mr. Díaz Ordaz. But it also placed Mr. Echeverría on a collision course with young leftists who chafed at one-party rule, censorship, a pro-business climate, and the strong influence of the United States.

The protesters had staged their demonstrations in the months leading up to the October 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City. Mr. Díaz Ordaz ordered that the protest movement be quelled in time for the Games, and Mr. Echeverría sent troops to break up campus sit-ins.

On Oct. 2, 1968, during a peaceful rally at the Tlatelolco housing development, soldiers and government security agents opened fire on the crowd. The government claimed that about 30 people died, but witnesses said that the number was as high as 300.

Mr. Echeverría had always denied that he ordered the shooting, arguing that the soldiers who carried out the attack were not under his command.

The Tlatelolco massacre ripped away the benevolent mask covering rule by the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, which had governed Mexico throughout most of the 20th century.

Mr. Echeverria in 2002 after meeting with prosecutors over his role in the repression of student protests in 1968 that led to a massacre. Credit…Jorge Uzon/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

As Octavio Paz, the Mexican writer and intellectual, observed: “At the very moment in which the Mexican government was receiving international recognition for 40 years of political stability and economic progress, a swash of blood dispelled the official optimism and caused every citizen to doubt the meaning of that progress.”

The wounds of Tlatelolco were still raw when Mr. Echeverría became president in 1970 with the avowed intention of carrying out what he called “a democratic opening.”

He promised industrial workers and the poor a more equitable share of the national wealth. He vowed to increase the state’s role in the economy. He began to sport the leather jackets of factory workers; his entourage dressed the same way. And the wives of politicians were asked to appear at state dinners in Mexican folk costumes instead of their usual haute couture gowns.

Mr. Echeverría was especially intent on co-opting the intellectuals. To a surprising extent, he succeeded. His speeches began to appropriate the leftist rhetoric used by dissenters during the 1968 crisis. He led Mexico into the third world camp, and championed the cause of developing countries in their economic dealings with industrialized nations. He spoke out against the growing power of multinational corporations, once even threatening to expel Coca-Cola from Mexico unless it revealed its secret formula to local bottlers.

Mr. Echeverría often disagreed with Washington over hemispheric affairs. He strengthened Mexico’s ties with Fidel Castro’s Cuba. He was a supporter of Salvador Allende, and when the Chilean president died in a 1973 military coup, Mr. Echeverría broke relations with the new right-wing government in Chile and welcomed thousands of political refugees from that country to Mexico. Under the Echeverría government, Mexico became the foremost haven for Latin American exiles.

Besides expressing ideological sympathy for intellectuals, the president offered them important jobs and financial inducements. After releasing protesters who were jailed in the 1968 crisis, he gave many of them government jobs. This signaled the beginning of a spectacular expansion of the bureaucracy. Between 1970 and 1976, public sector employment rose from 600,000 jobs to 2.2 million.

During Mr. Echeverría’s presidency and its immediate aftermath, affluence and social status transformed intellectuals into a privileged class who “lived better in Mexico than in the United States or Western Europe,” wrote Alan Riding, the New York Times’s Mexico correspondent during that era.

While the courting of left-wing intellectuals proved successful, Mr. Echeverría stuck to his former violent methods against the more radical left. Small, armed guerrilla groups were routinely suppressed by torture and assassination. Between 1971 and 1978, more than 400 people “disappeared.”

Under President Echeverría, relations between government and business reached their lowest ebb in decades.

The number of state-owned corporations mushroomed from 86 to 740. Taxes on corporate profits and personal incomes rose sharply. So did public spending on education, housing and agriculture. Between 1970 and 1976, the federal deficit soared by 600 percent. Inflation leaped by more than 20 percent a year. The balance of payments deficit tripled.

Business confidence was shattered. Billions of dollars fled across the border into real estate, banks, stocks and bonds in the United States. Shortly before Mr. Echeverría finished his term, the peso was devalued by more than 50 percent, bringing to a close 22 years of stable currency.

Upon taking office in 1970, Mr. Echeverría had vowed to “reduce the gap between the powerful and the unprotected.” Six years later, inflation and recession had widened the gap.

As the economy soured and public opinion turned against him, Mr. Echeverría’s behavior grew erratic. Previous presidents accepted lame-duck status and a lower profile during their final months in office. But he seemed more combative than ever, setting off rumors that he intended to stage a military coup and keep himself in office despite having already picked José López Portillo as his successor.

In July 1976, with just four months left in his term, Mr. Echeverría took control of Excélsior, then considered the country’s best newspaper, whose editorial columns had become increasingly critical of his presidency. Mr. Echeverría was soon embroiled in more controversy. He blamed anti-patriotic speculators for the devaluation of the peso, and as the currency continued to fall, he escalated his attacks against the business community.

With coup rumors at their peak in November 1976, only a month before the scheduled end of his term, the president expropriated hundreds of thousand of acres of rich farmlands and turned them over to militant peasants. The coup rumors vanished only with the inauguration of Mr. López Portillo on Dec. 1, 1976.

For several years after his presidency, Mr. Echeverría stayed out of Mexico, accepting distant diplomatic posts in Australia and New Zealand. He eventually returned to play a behind-the-scenes role as a left-wing gadfly in the PRI.

Then, beginning in 2000, Mr. Echeverría was thrust back into the public eye, after an opposition government began to investigate his role in the Tlatelolco massacre and in the killing of 25 student demonstrators in 1971 by a special police unit known as Los Halcones.

Mr. Echeverría was placed under house arrest in 2006. By 2007, the cases against him had been dismissed, though he was not released from house arrest until 2009, when appeals went in his favor.

Mr. Echeverría’s wife, María Esther Zuno, died in 1999. Complete information on survivors was not immediately available.

Elisabeth Malkin, Randal C. Archibold and Elda Lizzia Cantu contributed reporting.

READ MORE AT THE NEW YORK TIMES