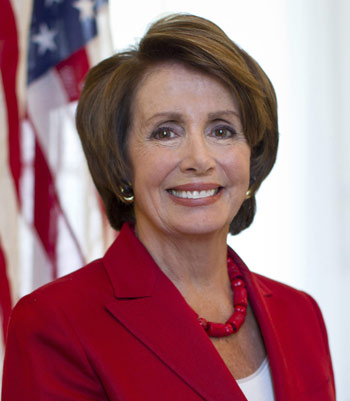

Speaker Pelosi’s Floor Speech on H.Res. 24, Impeaching Donald John Trump, President of the United States, for Incitement of Insurrection – Passed the House 232 to 197

H.Res.24 – Impeaching Donald John Trump, President of the United States, for high crimes and misdemeanors.

January 14, 2021 – Washington, D.C. – On Wednesday, Speaker Nancy Pelosi delivered remarks on the Floor of the House of Representatives in support of H.Res. 24,  impeaching Donald John Trump, President of the United States, for incitement of insurrection. Below are the Speaker’s remarks:

impeaching Donald John Trump, President of the United States, for incitement of insurrection. Below are the Speaker’s remarks:

Speaker Pelosi. Thank you, Madam Speaker. I thank the gentleman for yielding and for his leadership.

Madam Speaker, in his annual address to our predecessors in Congress, in 1862, President Abraham Lincoln spoke of the duty of the patriot in an hour of decisive crisis for the American people. ‘Fellow citizens,’ he said, ‘We cannot escape history. We will be remembered in spite of ourselves. No personal significance or insignificance, can spare one or another of us. The fiery trial through which we pass will light us down in honor or dishonor to the latest generation. We – even we here,’ he said, ‘hold the power and bear the responsibility.’

In the Bible, St. Paul wrote, ‘Think on these things.’ We must think on what Lincoln told us. We, even here – even us here – hold the power and bear the responsibility. We, you and I, hold in trust the power that derives most directly from the people of the United States, and we bear the responsibility to fulfill that oath that we all swear before God and before one another: the oath to defend the Constitution against all enemies foreign and domestic, so help us God.

We know that we face enemies of the Constitution. We know we experienced the insurrection that violated the sanctity of the people’s Capitol and attempted to overturn the duly recorded will of the American people. And we know that the President of the United States incited this insurrection, this armed rebellion, against our common country.

He must go. He is a clear and present danger to the nation that we all love. Since the presidential election in November – an election the President lost – he has repeatedly held about – lied about the outcome, sowed self-serving doubt about democracy and unconstitutionally sought to influence state officials to repeal reality. And, then, came that day of fire we all experienced.

The President must be impeached, and, I believe, the President must be convicted by the Senate, a constitutional remedy that will ensure that the republic will be safe from this man who is so resolutely determined to tear down the things that we hold dear and that hold us together.

It gives me no pleasure to say this. It breaks my heart. It should break your heart. It should break all of our hearts. For your presence in this hallowed Chamber is testament to your love for our country, for America, and to your faith in the work of our Founders to create a more perfect union.

Those insurrectionists were not patriots. They were not part of a political base to be catered to and managed. They were domestic terrorists, and justice must prevail.

But they did not appear out of a vacuum. They were sent here, sent here by the President, with words such as a cry to ‘fight like hell.’

Words matter. Truth matters. Accountability matters.

In his public exhortations to them, the President saw the insurrectionists not as the foes of freedom, as they are, but as the means to a terrible goal, the goal of his personally clinging to power. The goal of thwarting the will of the people. The goal of ending, in a fiery and bloody clash nearly two and a half centuries of our democracy.

This is not theoretical and this is not motivated by partisanship. I stand before you today as an officer of the Constitution, as Speaker of the House of Representatives. I stand before you as a wife, a mother, a grandmother, a daughter. A daughter whose father proudly served in this Congress: Thomas D’Alesandro, Jr. from Maryland. One of the first Italian Americans to serve in the Congress. And I stand here before you today as the noblest of things: a citizen of the United States of America.

With my voice and my vote, with a plea to all of you, Democrats and Republicans, I ask you to search your souls and answer these questions. Is the President’s war on democracy in keeping with the Constitution?

Were his words to an insurrectionary mob a high crime and misdemeanor?

Do we not have a duty to our oath to do all we Constitutionally can to protect our nation and our democracy from the appetites and ambitions of a man who has self-evidently demonstrated that he is a vital threat to liberty, to self-government and to the rule of law?

Our country is divided. We all know that. There are lies abroad in the land, spread by a desperate President who feels his power slipping away. We know that too. But I know this as well, that we here in this House have a sacred obligation to stand for truth, to stand up for the Constitution, to stand as guardians of the republic.

In a speech he was prepared to give in Dallas on Friday, November 22, 1963, President John F. Kennedy was to say, ‘We in this country, in this generation are, by destiny rather than choice, the watchmen on the walls of world freedom. We ask, therefore, that we may be worthy of our power and responsibility.’ That we may be worthy.

President Kennedy was assassinated before he could deliver those words to the nation, but they resonate more even now, in our time, in this place. Let us be worthy of our power and responsibility that what Lincoln thought was the world’s ‘last best hope,’ the United States of America, may long survive.

My fellow Members, my fellow Americans, we cannot escape history. Let us embrace our duty, fulfill our oath and honor the trust of our nation. And we pray that God will continue to bless America.

I thank you, Madam Speaker, and yield back.

Source: Speaker Nancy Pelosi