Mr. Guzmán, a onetime philosophy professor and longtime Communist Party member, traveled to China in the 1960s and became a devotee of Mao Zedong and the Cultural Revolution, a repressive movement meant to reorder Chinese society.

Calling himself “President Gonzalo,” Mr. Guzmán devised a set of principles based on Maoist thought as the guiding ideals of the Sendero Luminoso, or Shining Path, a term derived from an earlier leader of Peru’s Communist Party.

Building a stronghold at a provincial university in Ayacucho in the Andes Mountains, Mr. Guzmán proved to be a charismatic leader whose followers — mostly students and small farmers — considered him a godlike figure. They called him the Fourth Sword of Marxism, after Karl Marx, Russian revolutionary Vladimir Ilyich Lenin and Mao. A U.S. State Department official once described him as “Charlie Manson with an army.”

Mr. Guzmán advocated a violent takeover of Peruvian society, maintaining that true revolution would come only after crossing a “river of blood.” To him, even the Cuban regime of Fidel Castro and the Chinese leaders who succeeded Mao were too soft. His vision of nationalism resembled that of Cambodia’s Pol Pot, whose regime killed nearly a quarter of the country’s population.

“Judgment day has arrived,” he told his followers in 1980, just as the Shining Path’s effort to overthrow the country was beginning. “The future lies in guns and cannons.”

At first, Peruvian officials paid little attention to the movement, which began with the takeover of town halls in rural areas, bombings at polling stations and assassinations of local leaders. By 1981, Shining Path guerrillas had extended their reach to the capital of Lima, announcing their arrival in a particularly gruesome way: by hanging the carcasses of dozens of dead dogs from lampposts, as a warning to “capitalist dogs” and to anyone unwilling to follow Mr. Guzmán’s doctrinaire ideas.

“Violence is a universal law,” he said in 1988. “Without revolutionary violence . . . you can’t overthrow an old order to create a new one.”

Authorities seemed helpless against the Shining Path, as guerrillas disrupted Peru’s electrical system, food and water supplies. Police stations were raided for guns, and bombs were set off in theaters and restaurants, putting the entire nation, then numbering about 20 million people, on edge.

The group financed its widespread campaign of terror through bank robberies and by seizing airstrips used by drug dealers in remote parts of Peru. They demanded huge payoffs from cocaine kingpins, who appeared to be afraid of Mr. Guzmán’s guerrillas.

Kidnapping and murder were key parts of the Shining Path’s ruthless mode of operation, and bodies began to pile up around the country. The first large-scale massacre took place in 1983 in the town Lucanamarca, where 69 people — including the elderly and at least 18 children — were killed with machetes, axes and a vat of boiling water.

“The main thing was to make them understand that we were as tough as a bone, and ready to do anything,” Mr. Guzmán said afterward. “They were facing a different type of fighter.”

In 2003, a Peruvian truth and reconciliation commission determined that almost 70,000 people had been killed in the 1980s and 1990s — about half by Shining Path terrorists and the other half by the government’s police and military forces. Most of the victims were concentrated among Peru’s poor, Indigenous people in rural regions, where Mr. Guzmán had his strongest support.

For years, Mr. Guzmán remained a wraith, invisible to authorities whose efforts to capture him proved futile. By 1990, the Shining Path controlled a substantial part of the Peruvian highlands and countryside. More than 100 local officials had been assassinated in the preceding year, and a third of the country’s courts were idled because they did not have judges. Nearly three-quarters of the country was placed under a state of emergency or virtual martial law.

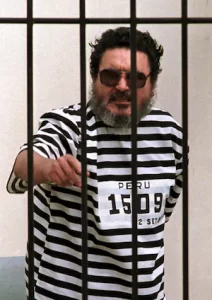

In 1990, Alberto Fujimori was elected Peru’s president, promising to snuff out the Shining Path and bring Mr. Guzmán to justice. On Sept. 12, 1992, in an operation later found to have been supported by the CIA, Peruvian police raided a house in a middle-class district of Lima, arresting Mr. Guzmán in his hiding place on the second floor above a dance studio. Photographers snapped pictures of him wearing a striped prison outfit, shouting revolutionary slogans in his cell. It was called the “capture of the century.”

After denouncing the notion of human rights, Mr. Guzmán changed his position a year later, when he was convicted of treason and sentenced to life in prison. His second-in-command in the Shining Path movement, Elena Iparraguirre, also received a life sentence. (She assumed her role after Mr. Guzmán’s first wife, Augusta La Torre, mysteriously died in 1988; there were suggestions that she was either murdered or died by suicide.)

Mr. Guzmán said the Shining Path movement would continue, but it soon fell apart without him.