The former police deputy remained defiant over the atrocities committed during the 1976-1983 military rule

His death, of undisclosed causes while receiving treatment under police guard, was announced by a court in La Plata, the capital of Buenos Aires province. That was the region where many of the teenage students were seized in 1976 as part of the junta’s sweeping repression against leftist opponents and other perceived enemies. Only four left custody alive.

The arc of Mr. Etchecolatz’s infamy, as a junta enforcer and later for his unrepentant defiance after Argentina’s return to democracy, was a study in the country’s struggle for a full reckoning over the atrocities committed during the dictatorship. Human rights groups estimate as many as 30,000 people were killed or “disappeared,” and many more were tortured in clandestine detention camps, some under the direction of Mr. Etchecolatz as police deputy for the Buenos Aires region.

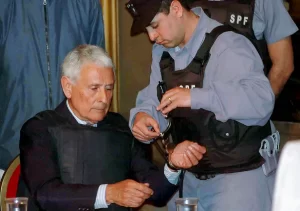

But Mr. Etchecolatz surrendered few secrets during a series of trials over the decades as crowds jeered him as a “killer” and “repressor,” once throwing red paint at him in 2006. A life-sentence judgment in that trial described him as complicit in “genocide,” a landmark ruling that, for the first time in Argentine jurisprudence, framed the “Dirty War” as fitting the United Nations definition for a genocidal campaign.

Mr. Etchecolatz, the conviction read, “was an essential part of an apparatus of destruction, death and terror.”

He refused to acknowledge the civilian courts’ authority, calling himself a prisoner of war or sometimes clutching a rosary and saying “only God” can judge him. Despite many opportunities, he also never offered any significant details to help account for the thousands still missing or give historians insights to piece together the junta’s complex web.

“I never had, or thought to have, or was haunted by, any sense of blame. For having killed? I was the executor of a law made by man,” he wrote in a 1988 autobiography, “La Otra Campaña del Nunca Más” (“The Other Never Again Campaign”). “I was the keeper of divine precepts. And I would do it again.” (The book title referred to Nunca Más, or Never Again, a national commission on state-directed human rights abuses during the junta.)

Mr. Etchecolatz, a chain smoker whose “investigative unit” ranged from street thugs to a Catholic priest who heard police confessions, became one of the most feared figures of the security apparatus. The junta took power at a time of near-total chaos: uncontrolled inflation and labor strikes as well as threats from leftist guerrillas and right-wing militias.

Mr. Etchecolatz appeared to have free rein to press the junta’s ruthless purges known as the National Reorganization Process, or simply “El Proceso.” More people were arrested or disappeared in Mr. Etchecolatz’s territory — the capital Buenos Aires and surrounding areas, including La Plata — than anywhere else in Argentina during the dictatorship’s early years, according to prosecutors.

An early shock was the Night of the Pencils. Over two days in September 1976, masked agents rounded up eight high school students — four boys and four girls — suspected of leftist sympathies. Two other male students were taken in other raids that month. They all were held in Mr. Etchecolatz’s gulag, prosecutors say, and six were never seen again by their families.

One of the surviving students, Pablo Diaz, said he received electric shocks to his mouth and genitals at a detention center known as Arana. He was 18 at the time. “They tore out a toenail,” he told investigators, according to the BBC. “It was very usual to spend several days without food.”

Democracy returned in 1983, after the military regime proved unable to steady a faltering economy and made a disastrous attempt to take the Falkland Islands, which Argentina claimed as part of its territory, from the British.

Mr. Etchecolatz was first convicted in 1986 during a wave of prosecutions against junta officials. But laws passed later that year gave amnesty for many security officers in attempts to avoid post-junta upheavals in the military and police. Mr. Etchecolatz and others convicted of Dirty War abuses were released.

Mr. Etchecolatz wrote his memoir, appeared on TV shows to confront accusers and mingled openly with past functionaries of the dictatorship, including his former boss, Gen. Ramón Camps, whose 25-year sentence also was put aside.

The amnesty was ordered repealed in 2003 by the government of President Néstor Kirchner, a leftist who had been briefly jailed during the junta years for his student activism. Mr. Etchecolatz was back in court the next year, under a civil trial not covered by the immunity.

This time, he and a police physician, Jorge Bergés, were convicted of roles in taking hundreds of infants of the families of “disappeared” or imprisoned parents and putting them up for adoption by junta supporters. Camps, who died in 1994, openly acknowledged the theft of babies “because subversive parents will raise subversive children.” Mr. Etchecolatz and Bergés were each sentenced to seven years.

In a separate trial in 2006, Mr. Etchecolatz became the first senior junta official tried for human rights abuses after Argentina’s high court approved lifting the amnesty. More than 100 witnesses were called, some describing in gruesome detail the conditions in the torture camps. Sitting in the front row were members of the group Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, women who held weekly vigils outside the presidential palace for their children and grandchildren who were lost during the dictatorship.

Judge Carlos Rozanski read the accusations of torture and disappearances. He then turned to Mr. Etchecolatz. Your profession? the judge asked.

“Retired policeman,” Mr. Etchecolatz calmly replied. He held a rosary and said he would not recognize the court’s jurisdiction, claiming he should face a military trial.

Months later, just before the judge read the life sentence, Mr. Etchecolatz rose with a hand-lettered sign around his neck. “Lord Jesus, if they condemn me, it is for following your cause,” it read.

The crowd in court cheered the sentence.

Miguel Osvaldo Etchecolatz was born in Azul, Argentina, on May 1, 1929. He rose through the police ranks and after the coup in 1976, moved into the inner circle of junta loyalists.

A complete list of survivors was not immediately available. At least one daughter, Mariana Dopazo, has been outspoken in her rejection of her father, changing her last name and condemning Mr. Etchecolatz and other junta leaders.

Almost two generations removed from the junta era, Mr. Etchecolatz remained a powerful symbol of the iron grip once held by the military and police. He was back in court multiple times to face Dirty War charges, most recently in 2020 with another life sentence for crimes that included torture in detention camps including one, Brigada Lanús, widely known as El Infierno, or hell.

Mr. Etchecolatz continued to stonewall prosecutors and others seeking any clues over the missing. Just once he appeared to open a door.

In a 2014 trial, reporters noticed Mr. Etchecolatz holding a slip of paper with a name, Jorge Julio López, a survivor of junta-era torture who vanished in 2006 before he was scheduled to testify against Mr. Etchecolatz. One the other side of the paper was written: Kidnap. López remains missing.

Rights groups and others alleged that sympathizers of Mr. Etchecolatz kidnapped López to intimidate other potential witnesses at future trials. The enigmatic note by Mr. Etchecolatz was widely interpreted as reinforcing the warning.

“The perpetrators of genocide continue to die without revealing their secrets, without telling us where [the disappeared] are or what they did with our relatives and disappeared comrades,” wrote Argentina’s environment minister, Juan Cabandié, in a tweet after Mr. Etchecolatz’s death. “Neither forget nor forgive.”

READ MORE AT THE WASHINGTON POST